Investors holding the banks as a safe yield play have had a wake up call courtesy of COVID-19. NAB have cut their dividend by over 60%, ANZ and Westpac have deferred their interim dividends and decide in August whether to make a payment.

Bank share prices have fallen by around a third since the February 2020 peak, but investors need to ask themselves whether they are in fact cheap, or do better opportunities exist elsewhere. The bank bulls would point to Australian bank shares trading at a lower book value than they have historically been, a common measure to value a bank.

Book value is determined simply by subtracting the banks liabilities from its assets and then dividing by the number of shares on issue. Nathan Bell (Portfolio Manager Intelligent Investor) highlights that Australian banks trade at a premium to their US and European peers on a price to book value. For example CBA currently trades at around 1.5 times book value, and 5 years ago traded at over 2.5 times book value. European Bank, ING trades at a book value of around 0.4 times. While Australian banks are trading at lower price to book values than they have been for some time, they are not necessarily cheap by global standards.

Matt Williams (Portfolio Manager, Airlie Funds Management) highlights that forecast Price to Earnings ratios for Australian banks in 2021 are 11.1, which makes them more expensive than UK banks at 8.2 times earnings and US banks at 10 times earnings.

One of the major risks to any bank relates to bad debts. The COVID-19 crisis now adds the spectre of a serious bad debt cycle.

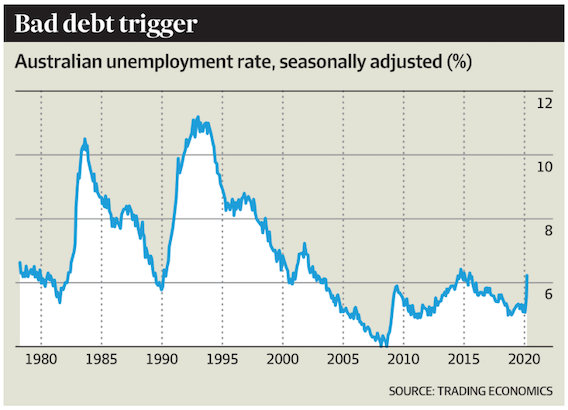

It seems universally accepted that COVID-19 will cause the first Australian recession in 30 years. Recessions increase unemployment and when people lose their jobs, their mortgage repayments can be at risk. The RBA is forecasting the unemployment rate to rise to around 10% during 2020, a level not seen since the 1990’s recession, and not even reached during GFC.

History of Australia’s unemployment rate

To put current provisioning for bad and doubtful debts into historical perspective Williams says “bad debts peaked at around 1% of gross loans following the 1990’s recession which compares to present day consensus forecasts for bad debts peaking in 2020 at 0.4% of gross loans. The current provisioning is materially lower than what happened in the 90’s recession and the GFC.”

The base assumptions around current consensus bad debts assume a multi year ‘U’ shaped recovery. Williams adds “If the recovery is more ‘V’ shaped and unemployment outcomes are better than feared then the banks are on the cheap side of fair”. Conversely, if unemployment outcomes turn out to be worse than expected, bank shares would most likely fare poorly.

Bell sees the small business sector as the source of the greatest risk to consensus forecasts on unemployment and bad debts. Small business is defined as those businesses with less than 20 employees. According to the ATO’s 2019 annual report, of the 4.2 million small businesses that operate in Australia, 800,000 of them had entered into a payment arrangement to pay their tax liability. That implies almost one in five small businesses couldn’t pay their tax bill, and that was before COVID-19 hit.

According to Australia’s Small Business Ombudsman report in 2019, Small business contributes around 33% to Australia’s economic output, and employs around 44% of all Australians. What happens to the small business sector matters a lot to the economy and to the unemployment rate. Unlike listed companies who can raise capital through the share market, small businesses have limited options which usually revolve around the owner mortgaging their home.

Bell says “we won’t know the final position until government support falls and loans stop being extended and we see the real impact of COVID-19 on the economy, particularly small business.”

He adds “the bull case for banks rests on investors being willing to pay a premium over book value despite single digit return on equity figures due to low interest rates. This has not been the case in major markets overseas, so it would be our version of Australian exceptionalism.”

Williams says the best environment for banks consists of slowly rising interest rates, low unemployment, strong migration resulting in economic growth, but those days appear over.

So while bank shares are cheaper than they have historically been, they are clearly not a risk free trade.

This article was written by Mark Draper (GEM Capital) and appeared in the Australian Financial Review in June 2020