Australian investors would be forgiven for largely ignoring the prospect of electric cars in their investment decision making with only 6,718 new electric vehicles (EV) sold in Australia during 2019 (includes fully electric EV, and plug in hybrid EV). For perspective, the total number of new vehicle sales in 2019 was 1,062,867. Astute investors however, are aware of the electric vehicle tsunami that is coming and are positioning to profit from it.

Alasdair McHugh (Director, Baillie Gifford) highlights “that currently only around 1% of the global passenger car fleet of 1.4 billion vehicles are electric. Therefore the opportunity for EV’s to replace the remaining 99% of passenger vehicles is substantial. Even against headwinds of ride-sharing, public transport developments and cycling/walking to work, the shift away from internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles to EV’s leaves a vast market to penetrate.”

Nick Markiewicz (Consumer Analyst, Platinum Asset Management) believes that the size of the EV market “will ultimately depend on the end goals of Governments and regulators, adoption rates of EV’s among consumers and how automakers choose to meet their targets”. While there is a wide range of views from credible pundits and automakers about EV penetration rates ranging from 10 – 60%, given the automotive sector is USD $2 trillion industry by turnover, even small adoption will still result in a large, high growth industry.

The most sophisticated market so far is China, which accounts for 47% of EV sales last year. The Chinese Government has a goal for 40% of all new car sales to be EV’s by 2030 according to Baillie Gifford.

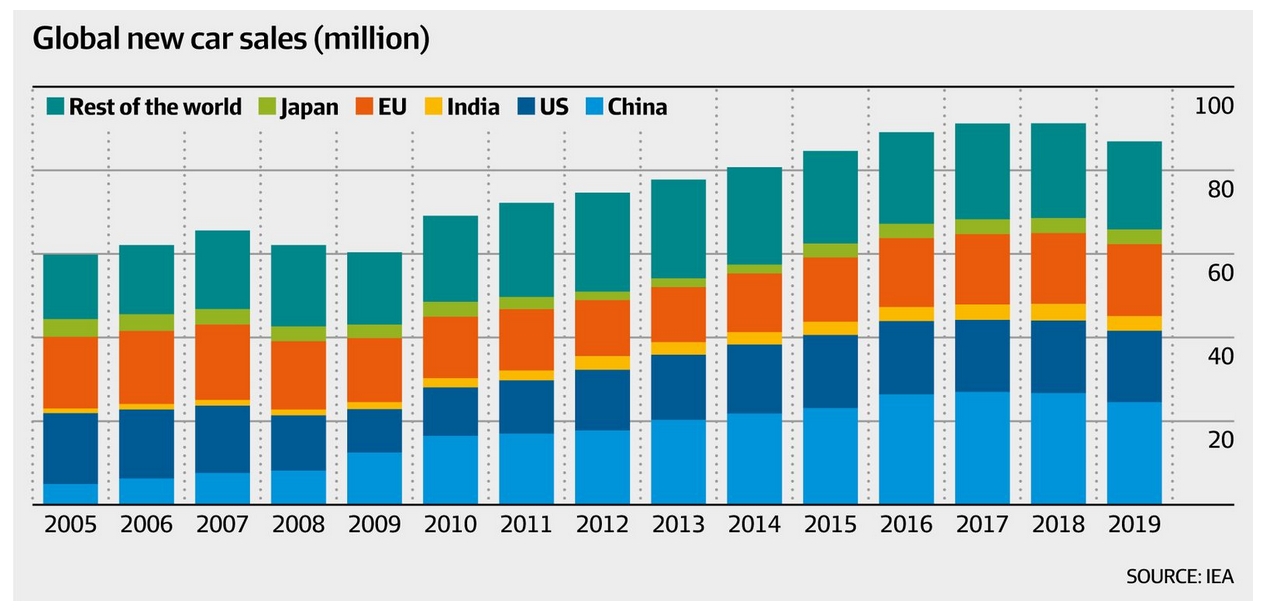

The chart below shows new car sales by region over the past 15 years.

Elsewhere in the world France has announced a ban on the sale of ICE vehicles from 2040 and in the UK, the ban will take effect from 2035.

Investors can seek to profit from the EV boom not just by owning high profile automakers such as Tesla, and Chinese automaker Nio, both owned by Baillie Gifford.

Markiewicz believes that traditional makers “like BMW and Toyota still have a relatively bright future, and do not deserve to trade at their current multiples. Both have deep electric vehicle expertise, with Toyota producing its revolutionary hybrid in 1997, and BMW launching the i3 in 2011. Unbeknown to many, BMW and Toyota are already two of the largest electric vehicle producers in the world”.

While the manufacture of EVs requires fewer mechanical parts than ICE vehicles, it does need many new electric and electronic components and batteries. Baillie Gifford like Samsung SDI in the battery supply chain and Platinum like LG Chem, who are battery producers. It is also interesting that EV cars are heavier resulting in increased tyre wear compared to conventional cars.

Some opportunity exists in Australia in owning resources companies who produce nickel, lithium and cobalt, which are used in battery production, alternatively investors can invest in managed funds to gain broader exposure to growth in electric vehicles.

The biggest threat, according to McHugh, to investing in the EV industry “is the emergence of a new type of energy efficient ‘fuel’ that could power cars, for example ‘electrofuels’. One possibility is hydrogen gas (H2) made with renewable electricity. At the moment there are scientific barriers to entry for this technology; storing the gas within the bodywork of a car is difficult and could be dangerous, and therefore expensive”.

Second order effects of EV’s that investors need to consider is the impact of EV’s on the demand for oil, and the oil price. Markiewicz says that the impact is “likely to be at the margin – there are 1.4bn passenger vehicles in the global car fleet which account for 20% of crude demand today. EVs are only 2% of new vehicle sales, and the global fleet only turns over every ~15 years. As a thought exercise, even if EVs were 50% of all new vehicle sales today, it would still take 15 years to displace 10% of the world’s oil demand (0.7% demand destruction per year). At the same time, oil demand will grow elsewhere. Hence, even under bullish scenarios for EVs, changes to oil demand are likely to be quite small – impairing growth, rather than absolute demand”.

Owning EV manufacturers may be the obvious investment for this thematic, but investing in other related components in the EV chain may be just as interesting.

This article was written by Mark Draper (GEM Capital) and featured in the Australian Financial Review in July 2020.