This article is reproduced with permission from Investsmart.

Welcome to Property Point, a podcast exploring all things related to property investment in Australia.

This week I’m speaking to Tim Lawless, Head of Research at CoreLogic Asia Pacific.

The CoreLogic home value index lost 0.5% in April. That’s after we saw a 0.7% fall in March, and a 0.9% fall in February.

Could this easing represent a turnaround to come?

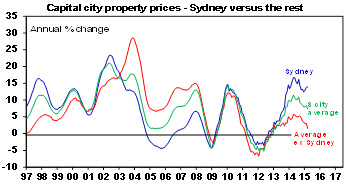

House price declines seem to have moderated in Sydney and Melbourne. However, there are signs of further price slippage elsewhere, outside of our two capitals.

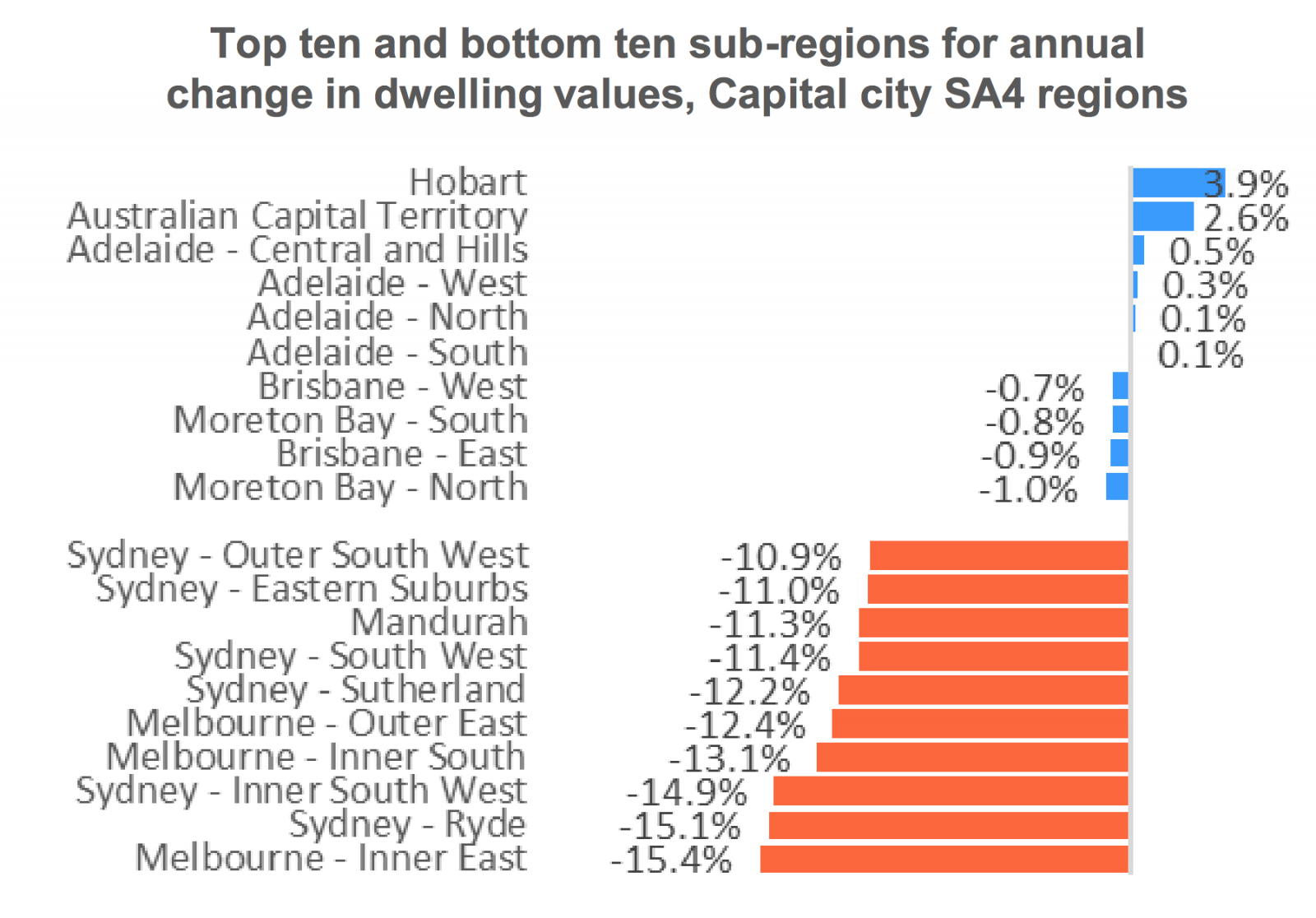

Sydney has come off 10.9% for the year and Melbourne has come off 10%. Prices are back to mid-2016 levels in both cities, and about 20-25% off their levels seen five years ago in 2014.

From the September 2017 peak, national house prices are now down nearly 10%.

Sydney and Melbourne read as much worse, down 14.5% and 10.9% from their peaks respectively. Melbourne’s price declines have now surpassed the 1989 downturn – in addition to 2004, 2008, 2010 and 2015's downturns.

The current price adjustment has now extended for 19 months.

Tim, this spot of data, being CoreLogic home values, finds itself in a very patchy narrative. Home sales volumes are at 23-year low, which was another set of data that came out this week, even though auction clearance rates have been holding steadier, in some pockets ticking up over the last little while. The big question, of course, in light of all of this, are you expecting further declines through the rest 2019 or have we seen the bottom?

Well, of course the market is very different from region to region. But broadly, yes, we are expecting values to continue falling across most areas of Australia. That's certainly been a most recent trend, although we aren't seeing values falling quite as quickly as what they were late last year or a bit earlier in 2019, it's quite clear that markets like Sydney and Melbourne are still seeing a fairly rapid rate of decline. In fact, our April figures showed Sydney values were down by 0.7 of a percent over the month, and Melbourne's down 0.6%. Not quite as bad as the nearly 2% month on month declines that we were seeing late last year, but still quite a material decline and we are also seeing the geographic scope of weakening conditions has expanded to include other capital cities, where values were generally rising previously.

And taking a broader view from that, so what are we seeing in terms of data standouts outside of Sydney and Melbourne? Is the troubled Perth turning around, or is Hobart continuing its upswing?

Well, touching on Perth, no, unfortunately, we're still seeing values falling in Perth. In fact, about a year and a half ago, we were seeing some signs that Perth was close to levelling out and values were holding relatively firm, but there has been a bit of a freshening of the downwards trend, which I think probably coincides with the tighter credit regime we're in at the moment as well as the fact that local economic conditions across WA still remain relatively soft. I could say the same things about NT and Darwin, as well.

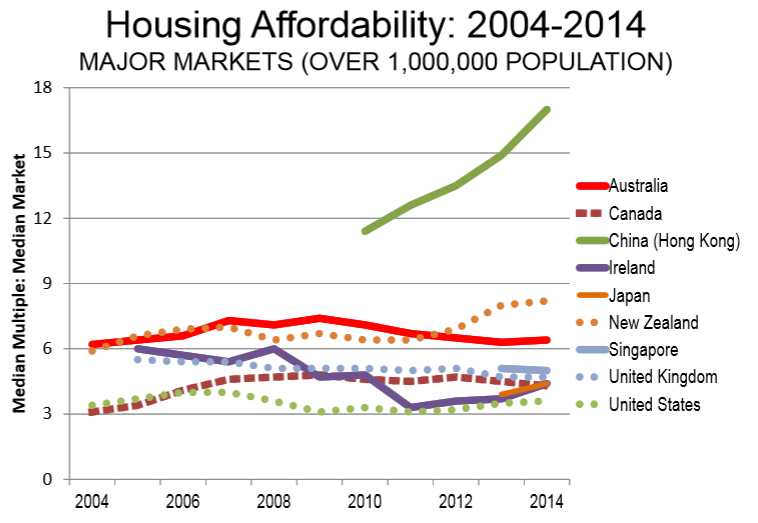

Interestingly enough, in Hobart, that really has been the standout market. It's the market where values having been trending higher quite quickly, but our April figures have shown had a bit of a crack in that façade, with values falling by nearly 1% over the month in Hobart, which I guess doesn't really come as much of a surprise considering that the growth rates were highly unsustainable in that marketplace. A bit more than a year ago values were rising at nearly at nearly 13% per annum, and now the annual rate of growth is just below 4% across Hobart and, of course, affordability constraints in that market have really deteriorated quite quickly.

Source: CoreLogic

Last year, I think most of the warnings were around apartments, particularly Melbourne and Brisbane. But now it seems like, to me, that everyone might have been worried about the wrong thing, where houses have actually shown a bigger price correction over the last year and the cycle to date. But is that just a function of the price run-up we saw in houses, as opposed to apartments? Or is there something more to it?

I think there's a few things happening here, and just to explain the numbers, looking at some of the largest cities. For example, we could write a pretty good case study, so Sydney house values over the past 12 months are down 11.8% and Sydney unit values are down by just over 9%, 9.1%. With a really similar story in Melbourne. So absolutely, unit values are falling, but not quite as much as what we've seen in the unit sector. So, I think what's driving that trend is a couple of things; one would be that we are seeing the market becoming very price sensitive, and of course apartments do offer up a much lower price point than detached housing. And the reason I think we are seeing this price sensitivity comes back to affordability issues in the most expensive markets. But probably more importantly is, I suppose, the change in the credit environment, where we are seeing lenders generally becoming much more cautious around high debt to income ratios and debt to loan ratios, which seems to be funnelling credit demand and credit availability toward that middle to low end of the market.

I think also with the surge first home buyer activity, particularly across Sydney and Melbourne, of course that segment of the marketplace is very price sensitive and I think that there is an anecdotal trend at least, where we're seeing more and more of first home buyers are willing to sacrifice their backyard and Hill’s hoist, and look for areas or housing stock that may be medium to high density, but located closer to where they're working, or where their family is, or closer to major transport nodes and so forth.

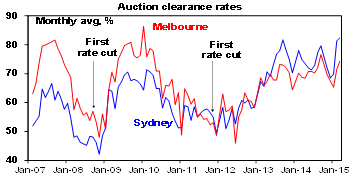

I'd like to just touch on clearance rates as well, which do remain at historically low levels. Several are making predictions, like JPMorgan, that clearance rates will remain below 50% for most of 2019. And elsewhere it’s been claimed that anything below 50% is a very weak result, and that it's evidence the market is still falling. But I've noticed that markets like Brisbane are actually consistently below 50% for clearance rates. So, what do you think about this? Is 50% nationally actually a tipping point? Or does it mean anything?

I think you can read a little bit too much into the national clearance rates. And, generally speaking, clearance rates are very, I suppose, important, very indicative of market conditions. In markets where auctions are still a very popular way of selling, and that's generally restricted to Melbourne, Sydney, and Canberra. Most other markets see a very small proportion of properties being taken to auction and auction clearance rates are much less indicative of broader market conditions, probably more indicative of what's happening in the premium sector where you generally find unique properties or distressed properties are taken to auction.

I think that when we look at auction clearance rates in say Sydney and Melbourne, to a lesser extent in Canberra, we're generally seeing the auction clearance rate holding around the mid to low 50% mark, which as you say is still very low. It does suggest that there is ongoing weakness in the market, but they are much better than what we were seeing at the end of last year, where auction clearance rates were down around the low 40% mark, even at one stage dipping below 40% in Sydney. I think that does coincide with this subtle improvement in the rate of decline that we've been seeing across Sydney and Melbourne over recent months. The market's still falling, but not as quite as severe as what it was. Auction clearance rates are still low, but not as quite as severe as what they were late last year.

Tim, looming large over property, of course, is the RBA, which is meeting next week. The RBA has raised the issue of negative equity. I'd like to ask you about this. I don't know whether too much attention is paid to negative equity, like you've said with clearance rates, given the context where as long as a household with a mortgage has an income and a job, the RBA has said they don't seem to think it'll be a problem. What's your view on the negative equity conundrum, where if house prices fall 25% nationally, I've read, it would put 850,000 home buyers in negative equity?

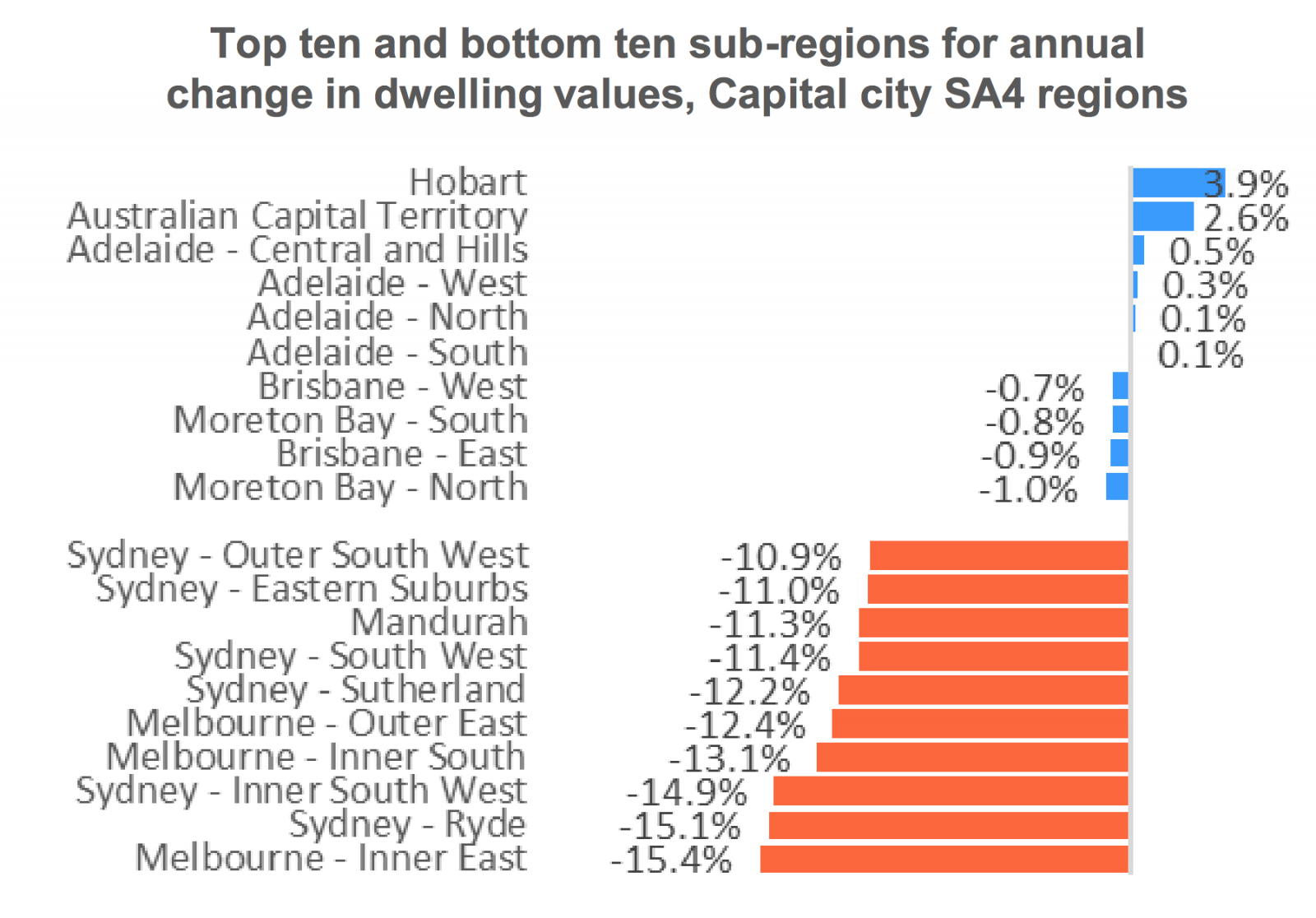

Yeah, that makes sense to me. It's actually quite an elusive statistic to obtain in Australia. Simply because there isn't a lot transparency or visibility on the debt side of individual home ownership. Quite clearly, in our data we can see how much values have fallen, how much values have changed, but we don't know how much deposit, for example, was held against individual properties. What we can see though that gives us a pretty firm hint around equity levels would be the areas around Australia where values have fallen by say more than 15 and more than 20%. So if I look around the subregion of the capital cities, there's only one region across the country based on statistical area 4s, SA4 regions, where values have fallen by more than 20%, and that's the Sydney area of Ryde, where values are down by 22.7%. You've also got areas like the inner south-west of Sydney, Sutherland Shire, the Hills District, the inner west and North Sydney, where values have fallen by more than 15%, and you could throw Parramatta in there as well.

In Melbourne, it would be the areas like the inner-east and the inner-south, which tend to be more exclusive markets, where values have fallen by more than 15%. When you have value declines of that magnitude, it's pretty clear that if you're a recent buyer to the marketplace, and so you did have a 15% to 20% deposit, then there will be some evidence of negative equity creeping into those markets.

Source: CoreLogic

How likely, Tim, do you think a rate cut is next week by the RBA? The market's pricing a 40% probability.

It's my view that we probably will see the RBA starting to position for a rate cut later this year, but probably not cut in the May meeting. Simply because I think cutting before the federal election may be a thing a difficult thing to do politically, not that the RBA has political ties. But also, the fact that I think the RBA probably will start changing their commentary to start setting up an expectation for a rate cut over coming months. Of course, we did see the very low inflation numbers, in fact, you know, the donut after the March quarter, but we're still reasonably strong labour market indicators, mostly emanating out of New South Wales and Victoria, of course. But I think that as we start to see labour markets potentially softening, as the residential construction sector in both those states starts to settle down, then maybe we might start to see more evidence of the labour market indicators, which is another key element of what the RBA is looking for before they cut, could start to soften out a little bit.

And another big question: Will rate cuts fire up housing again? Do you think that will be the catalyst?

I'm not too sure about that. Absolutely, if we do see rates coming down, and I think we probably will see rates move lower and then most of that being passed onto mortgage rates as well, but we still have a fairly substantial serviceability assessment as a barrier for a lot of borrowers. I don't think, even if we do see mortgage rates moving lower, it won't have the same stimulatory effect as what we've seen over previous periods when rates have come down. No doubt it's going to be a net positive for the marketplace, a lower cost of debt is always going to be positive, but I think there will be some prospective buyers out there who simply will still find that obtaining finance and getting through that credit assessment is going to be a barrier for a substantial or a mature enough lift in buying activity.

Do you expect that changes to negative gearing, should Labor get in at the federal level later this month, are they already factored into these changes in home prices? Or do you think an even bigger slide could happen if Labor does get in?

Well it's certainly an uncertainty, and I think the truth is that nobody really knows what the effect of these policy changes might be if we do see a change in government and they do get through to the senate. I think, generally speaking, if you remove an incentive from the marketplace, generally that's an overall net negative, and we'd expect there to be some dampening effect on investment activity in the market. To what extent that impacts on prices is really the great unknown. My expectation is if you take away some demand for the marketplace, it's likely to have some further downwards pressure on prices. Maybe that could be compensated by some upwards pressure from lower mortgage rates, improved affordability, and so forth as well. So overall, not too sure how that outcome's going to play out, but I think if we do see less investment of the marketplace, we potentially would see rental rates gradually starting to rise higher and I guess, encouraging that already evident trend where rental yields are moving higher, probably would result in higher rental yields longer term, alleviating the need for negative gearing in the first place.

I think the biggest question here is the adjustment period, if we do see these policies implemented, what's that adjustment period going to look like, and how much does it impact negatively on housing prices.

I might leave it at there for today with the great unknown. Thank you so much Tim, for the chat.

Thanks, it’s been a good chat, great interview. Thanks very much.

That was Tim Lawless, head of research at CoreLogic Asia Pacific.